While this may have been true in the context that Beauford was speaking—Burt could easily distinguish original Delaneys from copies or fraudulent pieces)—in fact, it is Beauford who “had the eye.” Whether or not he knew it consciously, we may never know. But one can certainly see it in his paintings, and particularly in his self-portraits.

In Beauford’s formative years as an artist, capturing likeness was his primary goal in portraiture. But during his New York years, he began to take painterly liberties with his portraits of Harlem residents, and in his Paris years, his portraits of others reflected his increasing concern with color and the “inner light” of his subjects in opposition to likeness. Author David Leeming cites an example of this attitude in Amazing Grace

If you wanted an exact likeness you could have gone to a photographer…when you sing you become eighteen again, and that’s what I wanted to capture.Peterson offered to buy the painting, but Beauford refused payment, giving the painting to his subject instead.

Sue Canterbury, curator of the Minneapolis Institute of Arts exposition entitled Beauford Delaney: From New York to Paris

In looking at a series of Beauford’s self-portraits, the astute observer will note that there is often asymmetry in Beauford’s eyes. This irregularity differs from portrait to portrait, and is not a reflection of any physical disfigurement in Beauford’s face. Perhaps this is Beauford's way, consciously or subconsciously, of depicting the two types of vision described above.

In his 1944 self-portrait, Beauford has represented his right eye as being entirely white. His left eye is larger than the right, rhomboid in shape, and one gets the impression that it has no lid. The pupil is light-colored and the surrounding iris black. In his 1950 self-portrait, it is the right eye that is smaller, with a black iris and no apparent pupil, while the left eye is a grayish tan with a clear tan iris and a dark pupil.

In his 1964 self-portrait, Beauford had retained the proportions that he used in his 1950 self-portrait. His face is gaunt, making the white of the almond-shaped left eye seem sunken in and the white of that eye more gleaming.

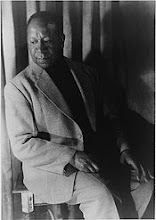

Self-portrait

Oil on canvas (1964)

Collection of the Reinfrank Family

In his 1972 portrait, he returns to marked asymmetry, this time accentuated by the fullness of his face. The left eye is larger and higher than the right, the iris is thin and the pupil large and light-colored—even mottled.

Self-portrait

Gouache on paper (1972)

Collection of David Leeming

Catherine St. John, a professor at Berkeley College in New Jersey and author of the essay “A Narrative of Belonging: The Art of Beauford Delaney and Glen Ligon,” describes the white eye in the 1944 self-portrait as “vacant,” and refers to the “monocular stare” that philosopher Jacques Derrida evoked in his Memoirs of the Blind: The Self-Portrait and Other Ruins – “a single eye open and fixed firmly on its own image, seeing nothing, nothing but an eye which prevents it from seeing anything at all.” St. John poses the rhetorical question “Are Delaney’s self-portraits attempts to find his own identity in his own image?”

In my opinion, Beauford’s numerous self-portraits are some of his most extraordinary oeuvre. (The ones presented here are but a few of them.) I encourage you to search for images of these works on line or to view them in person at museums and judge for yourself.