Romare Bearden, an African-American artist and writer, co-authored a book called A History of African-American Artists – from 1792 to the Present with Anglo-American journalist Harry Henderson. The book contains a brief chapter (seven pages) devoted to Beauford.

The chapter is primarily biographical, but there are also several scholarly descriptions of Beauford’s works. Bearden and Henderson include a frank criticism of Henry Miller’s essay “The Amazing and Invariable Beauford Delaney,” which they describe as a patronizing article that gives a false picture of Beauford as “a mindless, visionary artist.”

There are interesting tidbits of information about Beauford in this chapter and scattered throughout the book, such as the fact that Beauford’s parents named him after the town of Beaufort, South Carolina, from which they migrated during the Civil War. In the six-page chapter on Beauford’s brother Joseph, we learn that some 300 Americans attended Beauford’s funeral service at the American Church in Paris and that the pastor presiding over that service was from the brothers’ home state of Tennessee.

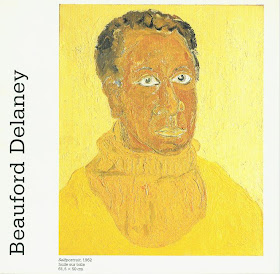

One of the color plates in the book displays Beauford’s portrait of James Baldwin entitled The Sage Black, and cites it as belonging to Mrs. James Jones of Sagaponack, N. Y. at the time the book was published. A black and white photo of Beauford’s 1962 self-portrait (below) is also cited as belonging to Mrs. Jones, who is undoubtedly the wife of writer James Jones, a great friend of Beauford during his Paris years.

Beauford’s 1962 self-portrait as shown on the invitation card of the

1992 Darthea Speyer exposition of Beauford’s works

Card courtesy of the Darthea Speyer Gallery

But my greatest discovery in perusing this book is a photo of a young Beauford looking over the shoulder of Palmer Hayden as Hayden paints at a 1930s outdoor art show in Washington Square in New York City.

It is rare to find photos of the young Beauford!

The chapter is primarily biographical, but there are also several scholarly descriptions of Beauford’s works. Bearden and Henderson include a frank criticism of Henry Miller’s essay “The Amazing and Invariable Beauford Delaney,” which they describe as a patronizing article that gives a false picture of Beauford as “a mindless, visionary artist.”

There are interesting tidbits of information about Beauford in this chapter and scattered throughout the book, such as the fact that Beauford’s parents named him after the town of Beaufort, South Carolina, from which they migrated during the Civil War. In the six-page chapter on Beauford’s brother Joseph, we learn that some 300 Americans attended Beauford’s funeral service at the American Church in Paris and that the pastor presiding over that service was from the brothers’ home state of Tennessee.

One of the color plates in the book displays Beauford’s portrait of James Baldwin entitled The Sage Black, and cites it as belonging to Mrs. James Jones of Sagaponack, N. Y. at the time the book was published. A black and white photo of Beauford’s 1962 self-portrait (below) is also cited as belonging to Mrs. Jones, who is undoubtedly the wife of writer James Jones, a great friend of Beauford during his Paris years.

1992 Darthea Speyer exposition of Beauford’s works

Card courtesy of the Darthea Speyer Gallery

But my greatest discovery in perusing this book is a photo of a young Beauford looking over the shoulder of Palmer Hayden as Hayden paints at a 1930s outdoor art show in Washington Square in New York City.

Palmer C. Hayden and Beauford Delaney at Washington Square, NYC (1930s)

Photo from the National Archives, Harmon Collection

It is rare to find photos of the young Beauford!